Circumventing the Geocentric: A Note on “Planetes: Extinction”

- June 19th, 2022

- Posted in Uncategorized

- By Verderber

- Write comment

(by Michael Verderber. This essay was written to be read during the talkback/ Q&A at the Texas State Museum of Asian Cultures, but it was not read due to time constraints.)

When mounting a science fiction play, I ran into a huge problem that all of my research did not prepare me for. I had picked up several books on astronomy terms, theories, and events, and I quickly realized that these were all geocentric points of view – literally and metaphorically.

At first glance, this play appears like many other science fiction works in which several humans go to terraform, but “Planetes: Extinction” is not exactly about that. It is designed to bait the reader and audience into thinking so. But it is about an alien life form called the Valgar that are are doing that. The audience is baited into thinking they are human due to the commonplace tendency of sci-fi to be about humans. Even the number of syllables in each line of poetry are nine – same number of planets in our solar system. All design.

However, the issue became one of navigation. We know that sailors, much like the Valgarians, use constellations to help themselves navigate. That is where the geocentric view comes into play (as opposed to heliocentric). However, the Valgarians could not use constellations for their own navigation as it is an invention of humans from the physical viewpoint of Earth. Perspective-wise, where they are from (Terruh; another bait name), a constellation like the Big Dipper would look like nothing but random scattered stars, depending on what part of space they are entering our galaxy from. Thus, I could have made up constellations that they created, but that felt insulting to science and legitimate constellations. I opted for quadrants instead.

So, I felt this loss of terminology; I felt like I needed to avoid the problem by circumventing that sort of man-made language and man-made terminology all together. It did make the script feel science-less, but from the perspective of a life form coming in from beyond Pluto and heading towards Earth, it makes sense that things are quite backwards. Several man-made terms, ideas, machinations, and others had to be weighed: should I include this for the sake of science that a human audience would understand? Or do I omit it for the sake of the Valgarians’ point of view, who have never been in this galaxy before?

I thought that writing the syllables would be the most difficult part of the development process, as every line of the work is in strictly 9 syllables. But it was the conceptualizing science from another intelligent life forms’ perspective that proved to be the most difficult.

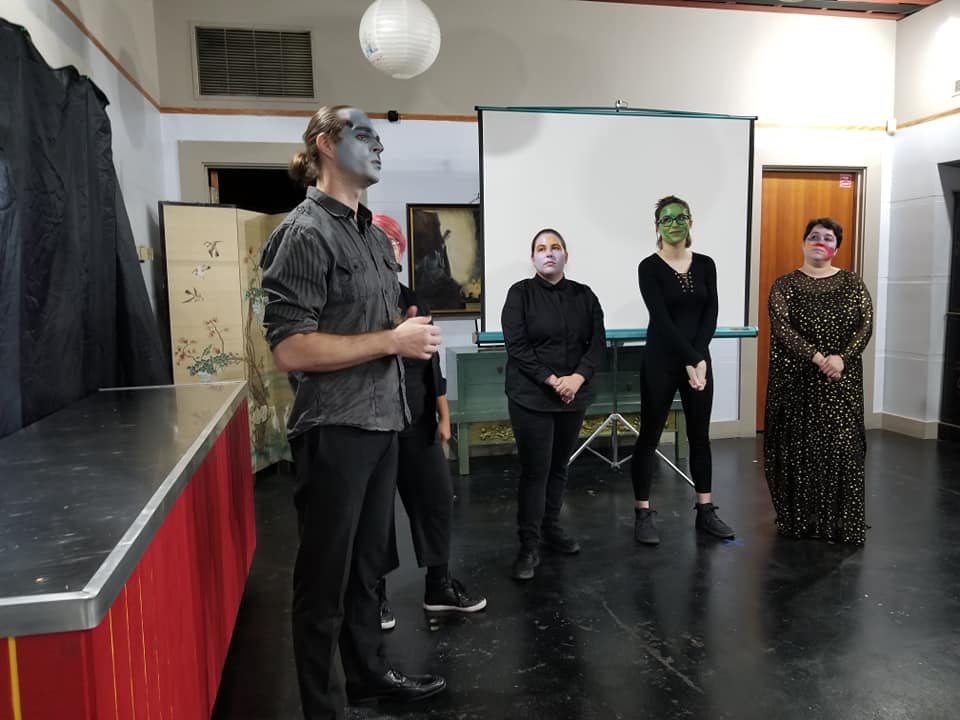

As you may have seen in the production, the actors mimed the usage of tools. We discussed the “alien” nature of these objects and tools. So, each actor was instructed to visualize and create a machine that their character would use for whichever task they were working on. On the second day of rehearsal, I stressed, “I don’t even want to know what your tool is!” I wanted to be as surprised as you may have been.

That notion brings me to the language and communication issues that the play brings to light. Through conversations with the production team, we talked at length one night that no matter how advanced we think we are as a human species, we still might not be able to communicate with another life form even at its the most basic level. Consider how many millions of species of animals there are on this planet alone. We cannot clearly communicate with any of them, but humans. Sure, we know what a dog’s bark might mean or what a cat probably wants when they rub up on our leg, but it is still not transparent communication. We are using conjecture to presume what they want: food, a walk, or attention.

That is just on a vocal and behavioral level. As one member of our crew mentioned: “plants talk” Presumably, what he meant was that flora and fauna use tacit modes of communication to assist each other, like how trees don’t entangle themselves with each other so that they can share equal lighting and nutrients. It’s called “crown shyness”. We have little idea how they just know that and how they communicate. So if we cannot even fully fathom crown shyness, we might be unable to to communicate with another species.

I suspect that when we do come in contact with another species, we might have the same communication issues we do with giraffes or any plants. Either their communication and language is so beyond our comprehension or we are beyond their levels of communication. It will probably be a matter of who lands on whose planet first. The smarter specie will prevail.

No comments yet.